To conclude her recent SGSAH internship, resident blogger Ebba Strutzenbladh reflects on her creative work at the Aberdeen City and Aberdeenshire Archives. She discusses how the City’s historical women inspired her fiction, balancing research with creative licence to maintain narrative tension, and unpacks the development of a tarot card deck based on Aberdeen’s medieval records.

My internship with the AC&AA this summer gave me the opportunity to spend three months exploring immersive ways to tell stories from Aberdeen’s history, mentored by historical fiction writer Victoria MacKenzie. Below, I reflect on the two major outcomes of my internship: the fiction I wrote and the tarot card deck I created, hoping to inspire others looking to engage people with their own research.

Writing fiction based on historical legal records

I wrote five short stories, each inspired by an object – or collection of objects – owned or claimed by an Aberdonian woman. Objects are rich starting points for stories; people treasure them, fight over them, pawn them in times of hardship, and lovingly pass them on. Paraphernalia (legal assets consisting of personal belongings) is often associated with women, as their legal claim to this type of property was historically strong.1 The objects in my stories range from what you might expect a wealthy medieval woman to own (a bracelet of coral beads, a silver brooch, and a pearl pendant) to seemingly mundane items (a padlock and a belt) and the entirely unexpected (a sword).

The woman who owned the sword was Cristina Smith, and her story serves as a prime example of my writing process. In terms of the ‘true’ story, Cristina claimed the sword alongside a workshop full of blacksmith’s tools on 22 November, 1501. She did so as the heir of Andrew Smith, who in one court entry is referred to as her father, and in another as her brother (legal records are often drawn up based on a scribe’s notes after the fact, leading to potential confusion). There is limited information about Cristina’s intentions; was she planning on taking over the workshop herself, or was she hoping to make a good marriage as the owner of a valuable workshop? Regardless, the goods legally belonged only to her in 1501, and she claimed them with assertiveness; she rallied all of the ‘best and worthiest blacksmiths of the town’, who came to court to confirm that Cristina ‘ought to’ have her inheritance.2 Perhaps someone had challenged her right to these objects, or else Cristina wanted it on paper that the male-coded objects in fact belonged to her, pre-empting any future challenges.3

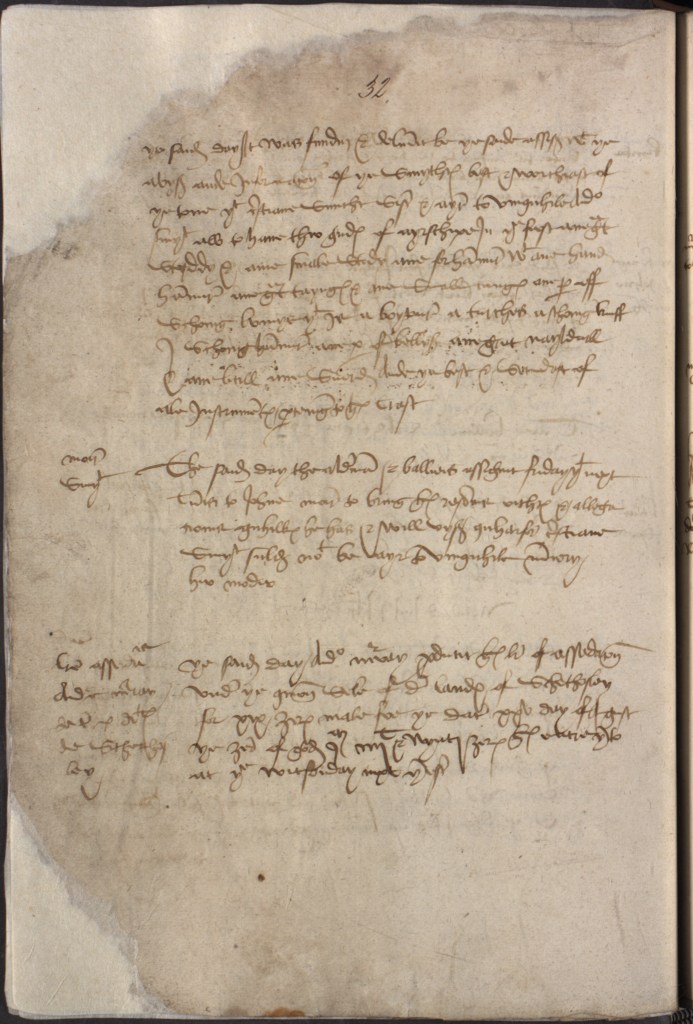

The first ten lines of this page describes Cristina’s appearance before the Burgh Court on 22 November. Based on the transcription on the ‘Search Aberdeen Registers’ website, I translated the entry from Older Scots to English and searched for other appearances by Cristina. Prior to 22 November, she was confirmed as the heir to both her mother and father, clearly eager to establish her rightful ownership of any goods associated with them.4 My interpretation based on her other court activities is that Cristina herself rallied the blacksmiths in support of her claim to the sword and blacksmith’s tools. Doing so suggests important guild contacts that she knew how to put on display. © Aberdeen City and Aberdeenshire Archives

Writing fiction is different from writing History: in the former, narrative tension comes first. In a historical essay, I would speculate whether Cristina was the heir to her father or her brother, as the records are unclear. I might also suggest that Cristina wasn’t interested in working independently as a blacksmith, but saw her inheritance as a means to secure a good marriage with an aspiring blacksmith, or was simply interested in the economic wealth that the tools represented. In this sense, a historical essay allows for many versions of the same person to exist before you reach a conclusion about them – you’re building a character with their subjectivity split into multiple parts. In a story, the narrative might collapse if you don’t take a stand on who your main character is and what they want. I wrote Cristina to challenge modern perceptions of medieval women, portraying her as a skilled blacksmith trained from a young age, with impressive muscles – something most medieval women would have had, as anyone who has tried to lift a medieval pot knows. It’s important to me to make the point, from time to time, that we have no reason to imagine medieval women through the nineteenth century lens of feminine frailty.

During the summer, I shared my stories and research process with artist Lisa Ross. We were both interested in the meaning of material objects, then and now, and what a modern reimagining of a medieval object might look like. During our collaboration, Lisa created several contemporary interpretations of the objects in my stories, including pendants, belts, and swords. She subsequently embarked this September on a master’s degree in creative practice at Gray’s School of Art where she will continue to explore questions around people’s relationship to materiality.

My stories are displayed on the Aberdeen Registers Website.

‘The Women’s Court’: My Tarot Card Deck

The second outcome of my internship was a deck of tarot cards that I named ‘The Women’s Court’. I wanted to create a fun and engaging way to present medieval history to a wider audience, and I initially thought the best way to do so was to use public spaces to showcase short snippets of my fiction. Few people I spoke to where enthused by the idea, and I had to reckon with a major difference between academic and public history: while writing the former often involves following your own mind, the latter almost by definition involves keeping your ear to the ground and listening to the movements of the crowd. Suddenly, it struck me that people around me have always been enthusiastic about tarot readings, which I’ve previously performed using a standard tarot card deck.

Tarot readings – where I let someone pick three random cards which I use to create a story about who they are – is a great way to connect with others. Like improv, this form of storytelling involves dialogue, flexibility, imagination, and risk-taking; I can’t prepare beforehand what cards will come up, so I have to be emotionally and intellectually present during the reading.

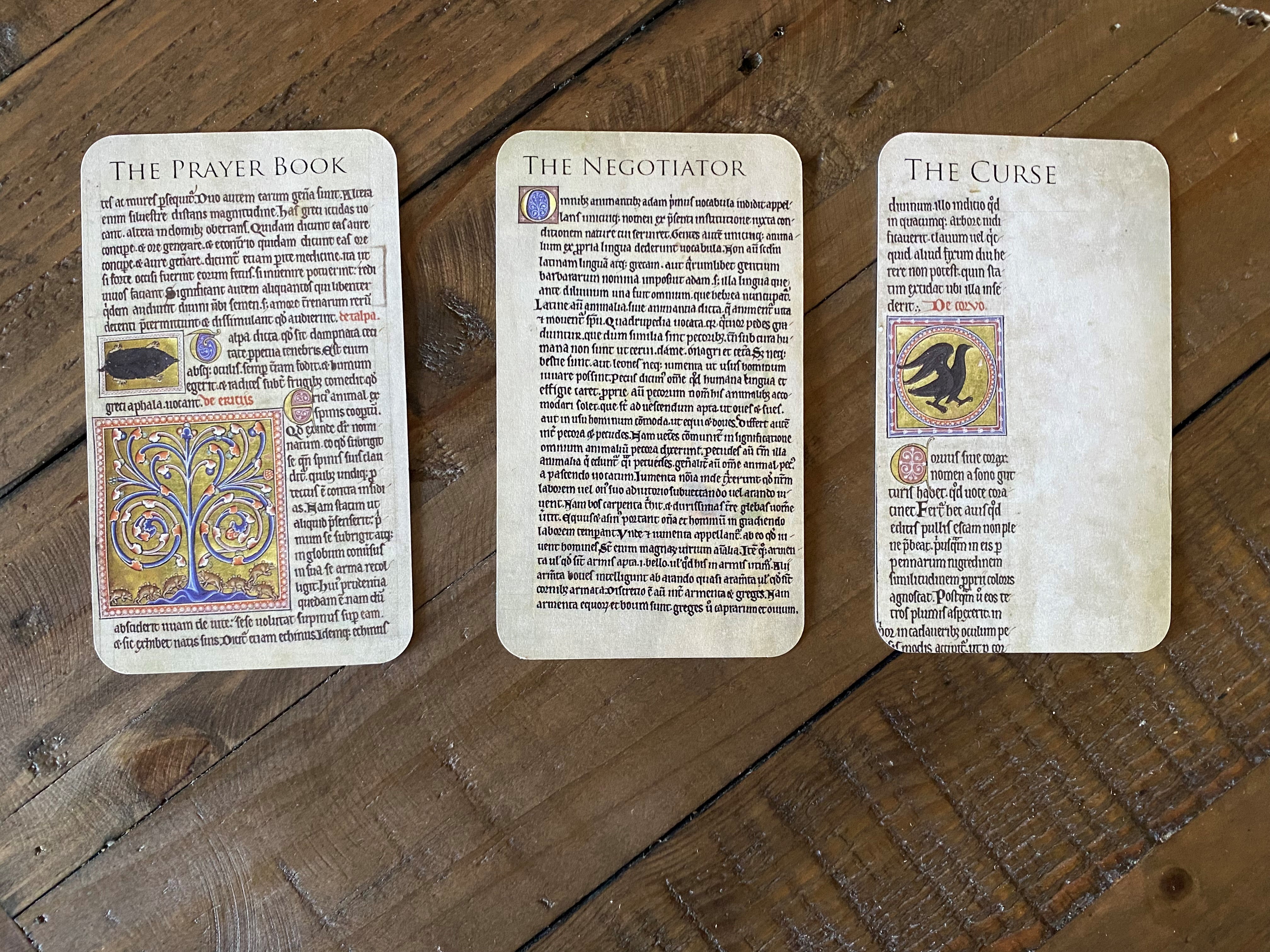

Based on the positive responses I received as a tarot reader in my networks in Aberdeen, I created a personalised deck inspired by the women who engaged with the law in the City’s distant past. I used illustrations from The Aberdeen Bestiary and The Burnet Psalter, both held by Aberdeen’s University Collections.5 I replaced the traditional tarot archetypes with various roles, legal strategies, objects, and ideas from Aberdeen’s fifteenth-century town council registers, held by the Aberdeen City and Aberdeenshire Archives. Answering the question ‘What kind of medieval woman are you?’, I created a format that allowed me to tell personalised stories that necessarily change with each reading.

I tried out the finished deck at the SGSAH 10-year anniversary on 3 October. The format was popular; not only was my showcase table frequently visited during the event, but afterwards at the pub, there was a line of people waiting to have their fortunes read – some were locals who got interested when they saw me read for other PGRs. The fact that I’ve received requests for additional readings at various events this autumn, including a reading at Glasgow’s Advanced Research Centre’s Halloween film screening of The Witches on 30 October, speaks to the enthusiasm people have for tarot readings.

If you’re interested in deconstructing the mystery of my readings, click the arrow to find more information about the composition and process of ‘The Women’s Court’.

Each tarot card deck consists of seventy-eight cards. The twenty-two Major Arcana cards suggest your journey through significant life events and spiritual lessons, representing key archetypes that shape your experiences. The fifty-six Minor Arcana cards introduce the everyday challenges, choices, and influences that guide your actions and decisions, providing insight into the more practical aspects of your life. In my deck, the minor arcana are divided into four suits: Relations, which explores the familial and social structures that define care and responsibility; Strategy, which delves into conflict, collaboration, and power dynamics; Material Wealth, representing tangible resources and possessions; and Legacy, focusing on what is passed down from generation to generation.

Each card is based on my interpretation of medieval life. For instance, the major arcana card ‘The Widow’, as I write in my 11-page guide, ‘highlights the need for a redefinition of self after a period of loss or change. However, the change might not be as significant as you first anticipated.’ This is because I don’t think widowhood should only be defined as a period of substantial change in a medieval woman’s life. Continuity is often more evident than change, as individuals didn’t rely solely on their spouses for companionship, support, and protection. Thinking in terms of this change-continuity binary usually proves fruitful when modern people think of their lives too. The combination of providing information about the distant past and opening up a conversation about what a person is currently experiencing often makes for a truly engaging conversation with plenty of parallels between medieval and modern life.

In terms of storytelling, picking three cards from a deck of seventy-eight can make for a range of narratives. Because the reading embarks from the question ‘What kind of medieval woman are you?’, some cards like ‘The Heiress’, ‘The Mother’, or ‘The Hostess’, lend themselves to more tangible stories, while others – like those in the Material Wealth category, including ‘The Spoon’, ‘The Prayer Book’, and ‘The Tapestry’ – can be more challenging to build a narrative around, though not impossible. The challenge of crafting a new story for each person keeps me on my toes, and I improve with each reading.

In conclusion

Facing the challenge of creating engaging stories has taught me a great deal about the two-sided nature of communication. I’ve learnt that public outreach should come from a place of curiosity, joy, and a willingness to take creative risks. If I’m not genuinely curious about what I’m doing, why should anyone else be? Additionally, I’ve learnt that committing to a particular idea or method too early in a creative process can prevent you from fully exploring other possibilities.

I encourage researchers reading this to get in touch with local archives or other institutions connected to their research to engage in playful, exploratory conversations with them, even if what comes from it won’t be a three-month internship. Building connections with local practitioners and others with an interest in research can lead to future opportunities. I’m already envisioning continuations of what I’ve done this summer, and I’ve only been back in traditional PhD study for a week.

Ebba Strutzenbladh is a PhD researcher at the University of Aberdeen, focusing on women’s engagement with the law in late medieval North-East Scotland. From July to early October 2024, she undertook a SGSAH internship at the Aberdeen City and Aberdeenshire Archives where she explored ways of presenting the Archive’s holdings to the public using immersive storytelling. She has previously published historical fiction in Causeway Magazine.

- Cordelia Beattie and Cathryn Spence, ‘Married Women, Testaments and Property in Sixteenth-Century Scotland’, The Scottish Historical Review 102 (2023), 1-33, 3; Rebecca Mason, ‘Married Women’s Testaments: Division and Distribution of Movable Property in Seventeenth-Century Glasgow’ in Annette Cremer (ed.), Gender, Law and Material Culture: Immobile Property and Mobile Goods in Early Modern Europe (London: Routledge, 2020), 65-90, 66, 70, 81. ↩︎

- ARO-8-0032-01, Edda Frankot, Anna Havinga, Claire Hawes, William Hepburn, Wim Peters, Jackson Armstrong, Phil Astley, Andrew Mackillop, Andrew Simpson, Adam Wyner, eds, Aberdeen Registers Online: 1398-1511 (Aberdeen: University of Aberdeen, 2019), <https://www.abdn.ac.uk/aro> [accessed 19/09/2024]. ↩︎

- The reason was possibly that a man called John Moir had challenged Cristina in court, though his concern was that Cristina should not be named the rightful heir to her mother; this separate court entry makes no mention of the sword or tools: ARO-8-0032-02. ↩︎

- ARO-8-0021-04; ARO-8-0040-03. ↩︎

- The Aberdeen Bestiary and The Burnet Psalter are licensed under Creative Commons Attribution Licence (CC-BY 4.0). ↩︎

5 thoughts on “Turning historical legal records into stories”