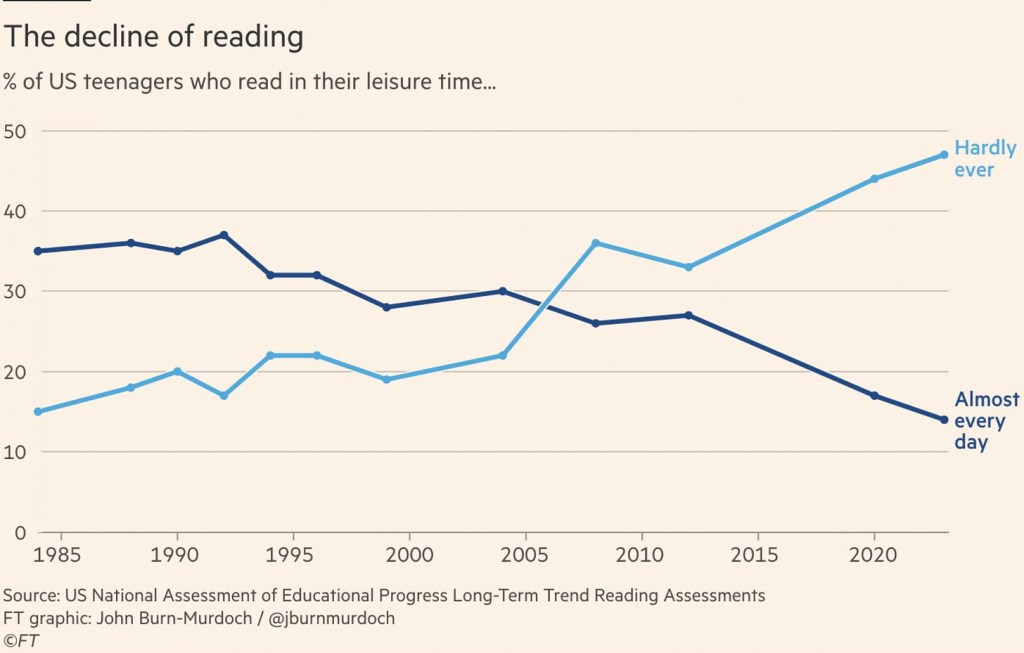

A few weeks ago, I wrote about AI, attention, cognitive offloading, and what this all means for academic research, writing, and teaching. Fixating on the perceived ‘death’ of critical thinking as we know it, I decided to finally read one of the many buzzworthy essays I’ve been meaning to tackle on my reading list: James Marriott’s “The dawn of the post literate society (and the end of civilisation).” Marriott’s musings live up to the promise of his title. The main thesis: literacy rates are declining and, therefore, so is intelligence, critical thinking, and the ability to effectively participate in democratic processes. He cites the invention of the smart phone as the main cause of this crisis, writing, “If the reading revolution represented the greatest transfer of knowledge to ordinary men and women in history, the screen revolution represents the greatest theft of knowledge from ordinary people in history.”1

Since 2005, there has been a steady decline in reading for pleasure among US teenagers. Image courtesy of The Financial Times and James Marriott.

He also explicitly mentions what universities and educational institutions are up against:

Our universities are at the front line of this crisis. They are now teaching their first truly “post-literate” cohorts of students, who have grown up almost entirely in the world of short-form video, computer games, addictive algorithms (and, increasingly, AI).

Because ubiquitous mobile internet has destroyed these students’ attention spans and restricted the growth of their vocabularies, the rich and detailed knowledge stored in books is becoming inaccessible to many of them.2

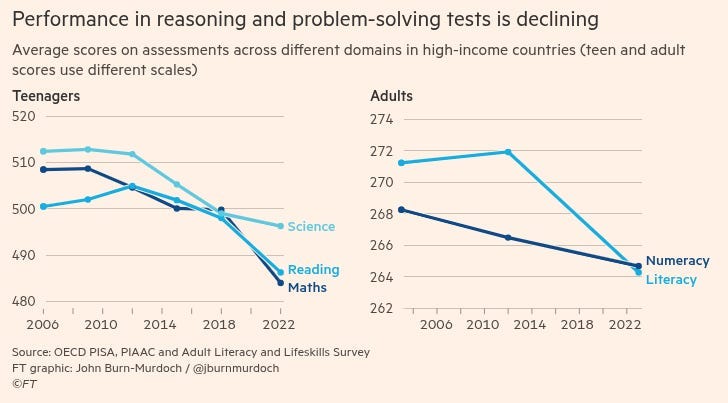

Citing late-breaking research on American undergraduate-level reading comprehension abilities and a newsworthy article from The Atlantic about university students’ utter inability to finish a book may add veracity to assumptions by previous academics.3 In fact, the argument against mobile phones has taken hold in Scottish primary schools, where Edinburgh Council’s successful smart phone ban trial4, for instance, saw favourable results. Anecdotally, I’ve witnessed many academics and teachers ‘gearing up’ for Generation Alpha– under the assumption that ‘AI’ has already wrecked their critical thinking abilities. Whether or not this is an accurate assumption, this ‘crisis’ will only grow in urgency as genAI continues to outpace previous technological developments.

Another collection of statistics from various organisations seem to suggest that test scores are on the decline in a number of domains that require key critical thinking skills. Graphic courtesy of The Financial Times and James Marriott.

On the other hand, crucial to Marriott’s argument is the notion that literature and the printed press are the only way that knowledge is disseminated– an idea with which many scholars in this community would take issue.5

In a previous post, I discussed the many headaches involved in publishing as an academic practice, but I also left out the expansive approaches taken to the publishing and dissemination of academic research.6 Especially within the realm of practice research, publishers and conference organisers are beginning to understand the value of different modalities of research presentation, allowing in audio-visual elements like photo essays, video essays, short films, performance-lectures, audio recordings, and more. Such stakeholders embrace that there is more than one way of communicating one’s research and, therefore, more than one way of ‘knowing’ another’s in turn. While the written word may be the most popular and ‘mainstream’ ways of communicating research, it is certainly not the only means for arts and humanities researchers.

David Lane’s “Art Workers,” which was recently presented at Edinburgh College of Art’s PhD Symposium and is a brilliant example of allowing in new forms of dissemination. Screenshot courtesy of @davidlaneartist.

Setting aside these tensions, how are we, as researchers, situated within this ‘post-literate society’? In a world in which “reading is in free-fall,” how do we justify the nature of our work? How do we develop innovative and robust scholarship that builds on the ‘giants’ who came before us when the world appears diametrically opposed to critical and meaningfully sustained intellectual engagement?

Personally, I am still living in this question. At times, I feel that I am living in an era that is incompatible with my own nuanced thought patterns and ‘question everything’ attitude. I find solace in academia for this very reason.

Marriott begins his article with a discussion of the printing press and the subsequent ‘reading revolution’ it provoked. In that revolution, we discovered a value for the written word and a value for that written world to travel. Now, Marriott argues, we have lost our personal value for the written word, the novel, and anything longer than the average TikTok video. But, I ask, what values have we gained this time around? Will we re-discover our value for print, or will we experiment with other modes that better support our new forms of attention? And even if we do experiment with new forms, will the value of the written word ever truly be lost on us?

- Marriott, J. (2025) ‘The dawn of the post-literate society’, Substack, 19 September. Available at: https://jmarriott.substack.com/p/the-dawn-of-the-post-literate-society-aa1 (Accessed: 28 October 2025). ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- See Haidt, J. (2024) The Anxious Generation: How the Great Rewiring of Childhood is Causing an Epidemic of Mental Illness. 1st Edition. Penguin Press. ↩︎

- Sullivan, J. (2025) ‘Mobile phones ban to come into force in Edinburgh’s primary schools following consultation’, The Scotsman, 3 September. Available at: https://www.edinburghnews.scotsman.com/news/mobile-phones-ban-to-come-into-force-in-edinburghs-primary-schools-following-consultation-5302014 (Accessed: 29 October 2025) ↩︎

- I realise the irony of this statement within the context of this online blog, which is a shorter, pithier alternative to the very medium Marriott wishes to re-promote. At the same time, such a ‘bite-size’ format might still be disparaged by him! ↩︎

- The specific publication venues and conferences where I have noticed this are far too numerous, but some fresh examples from my own area of research that accept expanded formats within their publication include Virtual Creativity and Body, Space & Technology. ↩︎