Dialogue is vital to the research community. Through our ‘In conversation with’ series, resident blogger Ebba Strutzenbladh explores different topics with guests in a dialogue format. This week she speaks to a fellow researcher, who has chosen to be referred to with the letters BB, about their experience being a refugee in Scotland, living in the midst of extreme political and cultural narratives, and recognising the value of the arts and humanities in trying times.

EBBA STRUTZENBLADH: I want to start off by asking what details of your life you’re willing to share with the readers.

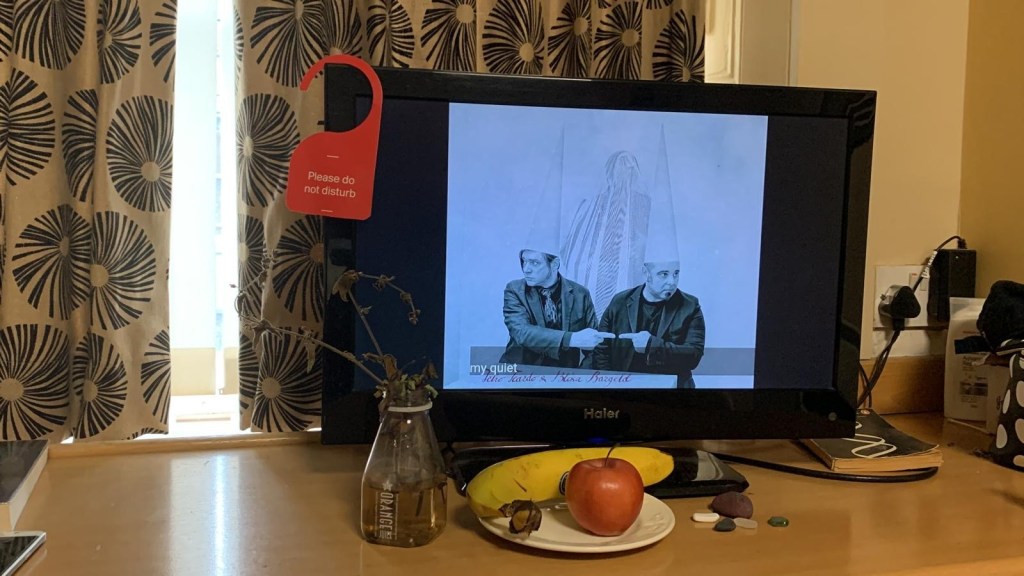

BB: Right now I’m living in what’s described by the council as temporary accommodation, in a hotel. I have been in Scotland for a little more than two years, and I came here seeking safety because of war in my country. Now I’m guaranteed refugee status here, but I had to wait two years before I got this guarantee. During these years I couldn’t legally work, so I had to volunteer. Before I left my country, I got a PhD degree there. Right now I’m looking for jobs in the health sector, and would consider working in academia too.

ES: These past few weeks have been a challenging political moment, considering the riots taking place in many UK cities. How has this time been for you, and what questions and concerns have been at the forefront of your mind?

BB: It has put me in a lot of stress, and I’m rethinking the future of living in this country. Also, although humans are the same wherever you go, they are defined by how they follow the law. When they abide by the law, they create an equal quality of living for all people residing in a country. I’m wondering, for the coming generations, what will happen for them, since even in countries that consider themselves developed, there are still people being led by hate.

ES: There are so many competing narratives about refugees on social and traditional media. It seems like the stories are always working with extremes: refugees are either saints or sinners, saviours of the economy or an eternal financial burden. I’m wondering what it’s like to live your life amongst all these fictions. Are these extremes contributing in any way to the shaping of your self-image? Or do the narratives feel too remote and abstract?

BB: I will start by saying that the media right now is very polarised, it has become like a business model. Refugees, as a topic, is something trendy. For polarisation to work, a lot of people need to be involved and discuss hot topics, and certain people want to show themselves ‘worthy’ to have a say in big debates. In this way, they’re creating two sides: people who stand with refugees and people who are against them. The idea of sinners and saints are created by these two sides. As a refugee, I can distinguish between people who are respecting humans as humans, and people who see humans as a material to do something else with. Right now, people in the media are taking advantage of our stories. Especially certain social media platforms are run by people who create their own rules for their companies, and they invest in people’s tragedies, anxieties, and addictions.

About the question of self-image, I think there is more opportunity now for refugees not to identify themselves with extremes. Understandings of borders and belonging are changing. Borders are man-made and have created a lot of inequality, and has drained resources for some parts of the world. People who are impacted by this scarcity, not least through the many wars going on right now, migrate no matter the circumstances because they have no choice. Even within Europe people are migrating, and these large groups of migrants will find new ways of communicating their experiences. In a way, refugees create their own ‘nations’, away from extreme stories of who they are. Refugees even had their own team in the Olympics, which represented them not as saints or sinners, but as something more.

At the same time, there are a lot of things happening in your mind – identity crises – as a human being, seeing these two extreme narratives play out. I’m thinking of generations coming after me, when they find themselves in the middle of this polarisation. I have memories of where I’m coming from and I know myself and my values, but if I had children, they would have roots in a place they don’t know. This is a question for historians: how do you help people like this find a place for themselves in history?

ES: I’ll be thinking about this for a long time for sure, especially since borders play such an important role in how historical sub-fields are traditionally delineated. As someone researching Scottish history, I’m curious to know more about what new residents of this country think of as important questions to investigate for the emerging generation of historians of Scotland. How would you speak to that?

BB: My question would be, how was respect seen in history? How was it defined, culturally, in terms of communication and relationships, and what can we learn from the past? History always carries information that we can use as a community. The question is how something is defined in the past and how it’s defined now. Historians use a lot of jargon and I just want a simple way of learning about respect and communication in the past, so I can understand better how to think about it in the present and in the future.

ES: More generally, how do you see the role of researchers in the arts and humanities in times like these?

BB: I think they have the potential to address misinformation about refugees and their experience, to make sure that the information is real and authentic on the news. When the riots happened, it happened because of misinformation. The information needs to be verified by someone.

ES: Do you think, though, that the people spreading the misinformation, and reading it, are active on parts of the internet that researchers don’t usually reach?

BB: Yes, right now people are active on many different platforms where management isn’t concerned with humanity’s welfare. There is no capacity for humanities researchers, who have good critical thinking skills and understand human feelings and decision making, to guide these platforms and share their expertise. This would involve them finding a new method of educating people, within or outside of the platforms creating polarisation. Be more creative and conduct more research on the effect of social media platforms and how to engage on there meaningfully. Make initiatives to work with the tech giants to try to pressure them to create new jobs within their structures, and the tech giants should take initiatives to employ humanities researchers.

ES: Thinking of the arts and humanities sector in Scotland at the moment, as opposed to how it might develop in the future, what cultural and heritage spaces or events have made you feel safe and welcome these past two years?

BB: I like the Burn’s dinner, which shows me Scottish people being poetic, organised and creative as they celebrate their culture. I like the song The Wild Mountain Thyme. In pubs, I’ve heard it sung to bagpipes and with the singer wearing a kilt. I think this kind of ceremonial event with kilts gives Scottish people the goose bumps. For me, I like exploring traditional Scottish culture, and I think it’s important to do so as you meet a new society through visiting their museums and read about their history, so you understand where they’re coming from. This will help you integrate well with them, and to find a common ground to communicate.

ES: Do you find that Scottish culture reminds you of your own?

BB: Yes! It makes me feel nostalgic for my country and brings back memories. Burn’s poetry reminds me of the poetry in my own language that I used to listen to in cafes. But I also explore new things here. I’ve participated in a lot of activities that allow you to reflect what’s inside. For example, I did a workshop that required me to represent in art how I react to micro aggression, so I tried to reflect how I keep calm when I’m met with this kind of behaviour through decorating a lamp shade in beautiful colours.

ES: Thank you so much for this enlightening chat, I really appreciate you taking the time to talk to me. What is the final thought you’d like to leave the reader with?

BB: I want to say, we need to find ways to reveal our common humanity and to not exclude anyone from that humanity, no matter what opinions they express on social media, and to remember mutual respect as the central aspect of communication. Talking is never dangerous, if there is respect.

Photos by BB.