This week, Joyce Fungo reflects on the inequalities that inevitably shape knowledge production within the field of Philosophy and in academia more generally, which became evident to her when she moved from the Philippines to Scotland to do her PhD in 2021.

One of the things I wish they had told me before getting into my PhD in the Philosophy programme at the University of Aberdeen is this: you won’t save the world with your PhD.

I realise now how anthropocentric this idea is, to start a PhD with self-interested motivations of making a mark in this dense, heavily congested space of knowledge pursuers. To navigate it alone is already quite the task, but even more so when the one doing the navigating is an obvious trespasser; when I think of anyone with the description of ‘philosopher’, I don’t quite fit the bill. In 2021, I made my move from one world to another, thinking it was a move from place of origin to destination, but there was no leaving my origin behind.

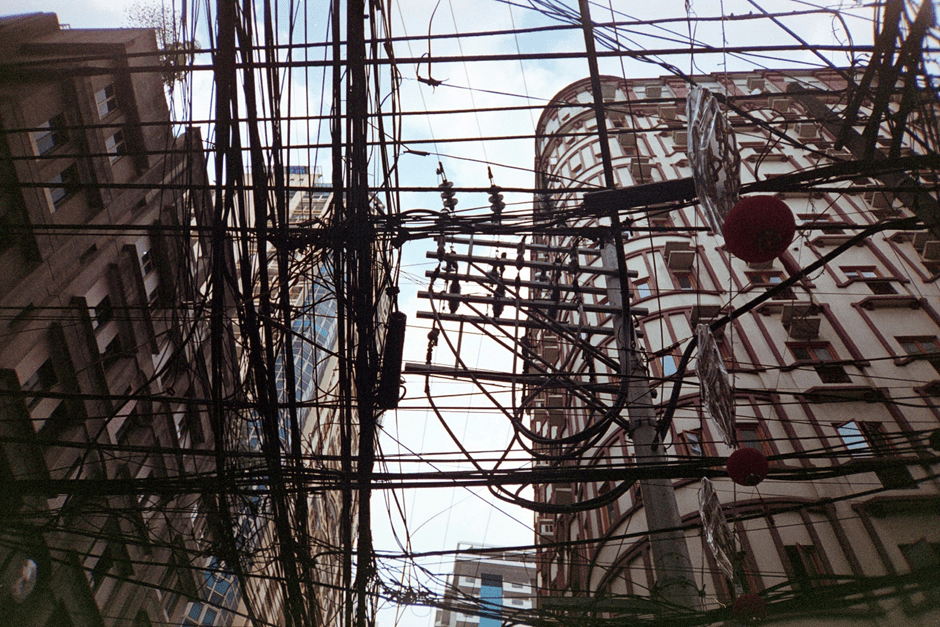

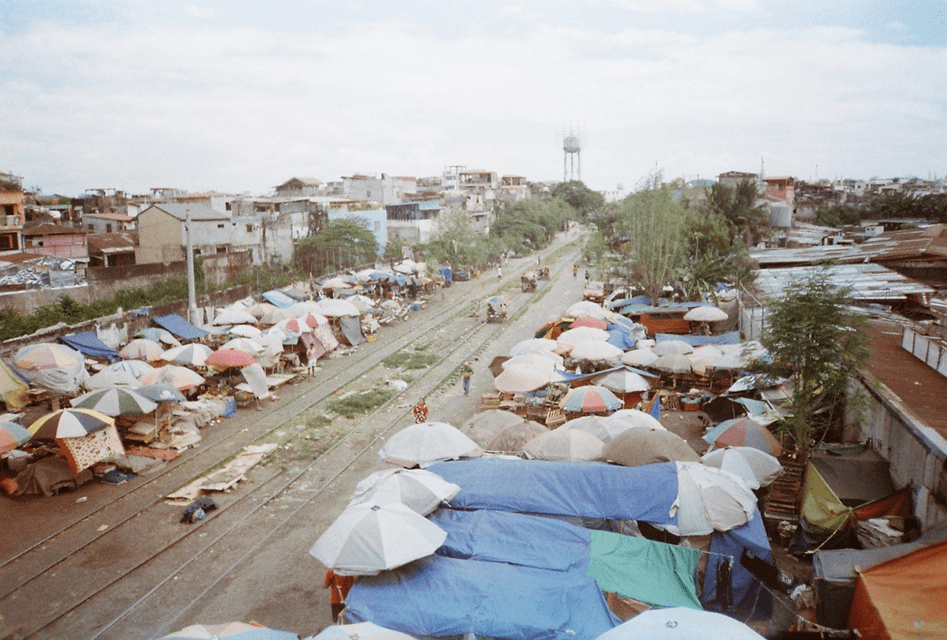

I did my Bachelor of Arts in Philosophy in a state university in Manila, Philippines, where 25°C is celebrated for the comfort it provides, a break from the routinary perspirations of boiling daily commutes. Only when I moved to Scotland did I truly understand how much weather conditions, heat, navigable and walkable roads, access to resources that are at the centre of academia (from books, to places, to people with names recognizable in universities and publishing houses that matter), altogether determine one’s intellectual production: how much you can produce, the tone of your writing, and what you will be writing about. I wonder now what the causal relationship is between one’s proximity to intolerable social conditions and one’s ability to write with vigour about things that matter.

When in Manila, I did what Manileños do. Well, in 2013, I did what students at the Polytechnic University of the Philippines do. Amid your not-so-typical megaphone-amplified acoustics of outcries from student activists who had likely overextended their stay in university for at least 7 years, I read Gilles Deleuze, a supposedly prolific Western thinker that I should know about because it should add to my cultural capital – at least if we considered the very specifics of where I was situated. At the time, it felt warranted because the name had an air of prestige attached to it, and its inaccessibility set apart the serious philosophy students (who held on to the basic rule that the more abstract and obscure the writing, the more prestigious it is) from the ones who are trying to make philosophy more applicable at the expense of losing the philosophy in it. If only I had encountered Kristie Dotson’s “How is this paper philosophy?” back then, to realise that there is no need to pander to an imagined high council of philosophers that dictate what counts as prestigious philosophy and what doesn’t.

In March 2013, I took my written examination in logic without a desk because the campus armchairs were being burnt in front of the campus’ iconic Intramuros-like wall as they were protesting the move to raise tuition fees. At the time, I was paying the equivalent of £10 every six months, and we demanded that it stayed that way (it did).

I got my bachelor’s degree from the same university in 2016, a momentous year for Filipinos everywhere: the year Rodrigo Duterte was elected president. Within the first year of his presidency, countless victims of extrajudicial killings where ordinary Filipino citizens who were framed as drug abusers were at his mercy. The average Filipino was not safe and there was no obvious logic that should tell us who will be at the wrong end of this malicious notion of justice. It became clear to me that the limitations of doing academic philosophy were responsible for why I always felt like I was reaching whenever I tried to write something about the most pressing concerns of my community. I had been using abstractions and idealisations to escape my society rather than to confront and understand it better. It was misguided and selfish. There are actual lives (and deaths) beyond just the theories of justice that my work could ever hope to justifiably represent.

I had such a romantic, self-involved vision of saving the world. I saw my peers from the departments of Sociology, Creative Writing, and Political Science come as one whenever the need for protest arose – they forgot their ideological differences and risked their academic standing, reputation, and safety. Of course, in retrospect, my memory is partly fabricated by layers of romanticisation. I forget about the internal fights, the moments when the heterogeneity of these small movements was more of a liability than an asset, and the undeniable performativity of the activism in many of its members. And I was never a part of it, I was an outsider looking in. Still, I had high hopes that contributing to knowledge production, with what little role I could play, could somehow make that world a better place, even at the risk of sounding naïve. After all, the first time I ever witnessed anyone fighting for something bigger than themselves was in the university.

The world is more complicated than the one my eighteen-year-old self had in mind. It does not need saving, and if it does, it won’t be by me in my armchair writing about epistemic value.

My PhD needs saving, though.

Collection of photos in Manila by Gerard Arcamo.

Joyce Fungo is a third-year PhD researcher at the University of Aberdeen whose project addresses the question of how the value of epistemic states, like knowledge and understanding, can be analysed from a non-ideal point of view. She can be found on LinkedIn.

This feels so right when I read it! Mostly things that need to be done are not done through writing a PhD. This is one of the reasons why I put my ideas for doing a PhD on hold. I feel like I have much more agency when I’m not tied down to reading articles and writing things that likely will never be read by more than a handful of people. Field experts definitely have a lot more opportunities than armchair experts.

LikeLike