Resident blogger Ebba Strutzenbladh reflects on the tourist/student lifestyle. Are our campuses there to be admired, or are researchers in a unique position to shed light on power and placehood?

A while back, a friend and fellow researcher from Glasgow visited me in Aberdeen. After touring Old Aberdeen—St Machar’s Cathedral, Seaton Park, and the university campus—he said, ‘I never understood why you’d choose to live here, but now I see. Aberdeen’s nice.’

His comment interested me. I started to reflect on why students pick their institutions, and the impact of a place’s appearance on that choice. While finding the right supervisor or access to specific resources tend to determine these decisions, other desires, fantasies and aims are often at play. At nineteen, I had a careers advisor at Lund University try to persuade me to do my undergraduate degree at her institution. Once I’d explained my attraction to the rolling Aberdeenshire hills and the chance for weekly trips to the Highlands, she at last acknowledged, ‘I understand. It’s a lifestyle choice, isn’t it?’

I’d never been to Aberdeen when I was nineteen. On arrival, I wasn’t sure what to make of it. Old Aberdeen, with its medieval King’s College, reminded me of ancient English cities I’d seen on TV, while New Aberdeen’s granite buildings had a distinct architectural identity that equally reminded me that I was no longer in a southern Swedish small town.

Despite my imagined trips to the Highlands, I ended up visiting that region less than once a year, buried in books from Fresher’s week until my thesis submission. My student experience was significantly less geographically situated than I had hoped, though my studies gave me a strong sense that Scotland’s legacy, often seen as a subset of English history, was warped by tourist expectations of an idealised Scottishness, while too often overlooked financially by Westminster.

In 2019, I took a one-year break from Scotland to do a master’s in Women’s Studies at Oxford, supported by a small bursary from Aberdeen – possibly because I’d expressed my desire to return to Scotland for a PhD, planning to apply feminist methodologies to Scottish materials.

While the methodological tools I encountered during my year away have been and continue to be invaluable, my social life at Oxford was defined by one thing only: tourism. The city is filled with tourists year-round. Students wearing the classic gowns are photographed as they pass through like statues who’ve come to life to amuse the town’s visitors. Students also participate in this university tourism by attending formal dinners at other colleges: ‘Let’s go to the one with the Harry Potter dining hall, ‘ people would say. I did my best to visit all the must-see spots, but by the year’s end, I was embarrassed at how much my social experience had revolved around the aim to inhabit famous or picturesque places. Why should I see the pub where Tolkien used to drink or a shop dedicated to Alice in Wonderland? The point of these stories, of the fantasy genre, is that they exist in our imaginations, that it’s impossible for us to visit them.

In Oxford and elsewhere, I’ve heard baffling comments from other students about Aberdeen: people who’d never been here confidently described it as deserted, remote, or even unattractive. Having spent my first four months in Oxford sick from the air pollution (the town’s in a valley and the pollution has nowhere to go) and constantly moody due to the challenges of paying three-times my Scottish rent for a shoebox room, I couldn’t believe that pursuers of humanist knowledge would so readily label one place as good and another as bad. The postcard-esque scenery of Oxford was taken to be the model against which other places must be measured.

Back in Aberdeen for my PhD, I forgot Oxford’s pollution. The destitute state of much of the city, intensified by the pandemic, saddened me. Gradually, due to my PhD being a local study of Aberdeenshire, I developed an interest in its regional culture. I became a tourist of the North-East. I visited Ballater, Braemar, the Cairngorms, Elgin, Fraserburgh, Peterhead. I moved to Stonehaven to immerse myself in the countryside. I volunteered with Befriend a Child to give some of my time to the Aberdonian community. I took hundreds of photos.

I soon realised that someone else had already taken the journey around Aberdeenshire: the royal family. At Ballater station, where the Queen’s train was memorialised until a recent fire, it became clear that Aberdeenshire is a popular tourist spot for those who idolise royal culture. They just skip Aberdeen itself, where the cityscape is marked by poverty and local businesses struggle to get by.

I was once told by an Aberdonian: ‘People in the countryside wear tweed to “blend in”. No one else around here would ever wear that, but they think they look Scottish.’ Imagine if some spent less cash on tweed and corgi dogs, and more on relocating to Aberdeen—a city in need of far more resources than its royally coded hinterlands.

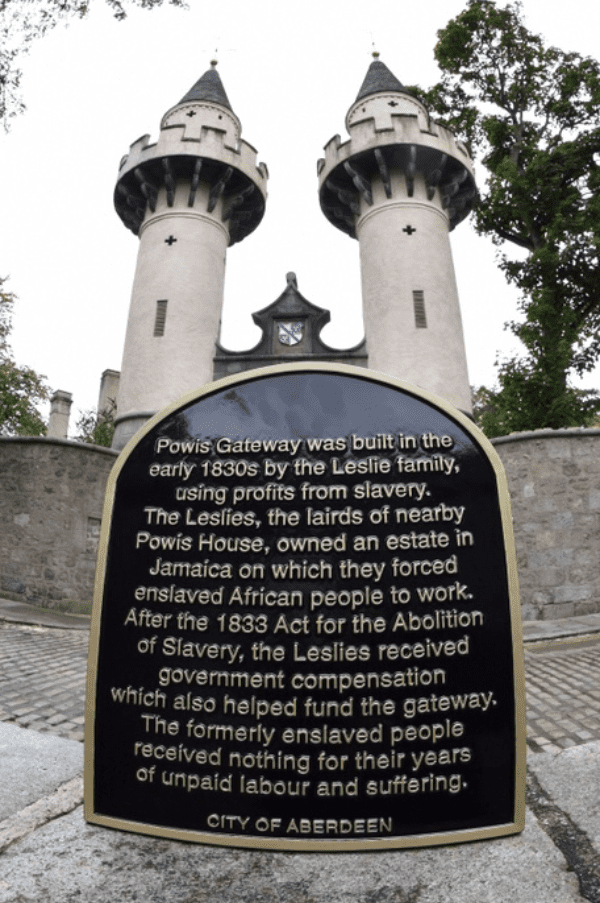

I no longer want to be a tourist. The tourist mindset assumes an entitlement to beauty without taking responsibility for what it means to share a place’s resources. For too long, I’ve been confused as to what my status is in this country; a student is somewhere between a local and a visitor, and it’s easy to forget that we live here on the same terms as everyone else. And there of course comes a time when every graduate, especially those at ancient institutions, must ask themselves: Where did my institution find the resources to build this picturesque campus? And where is it directing its resources today?

© University of Aberdeen

These days, Scottish universities are hiring student content creators to sell images of what life at their institutions are like. On social media, institutions around the country are posting pictures of their most picturesque buildings. University life is being reduced to a (virtual) postcard. But behind rolling hills and ancient buildings are real people with a real past – and an uncertain future.

Photos my own unless stated otherwise.

Very insightful, and the final paragraph drives the point very well. I based my university choices partly on location, though the quality of the degree programme I think still played the main role (at least I’d like to think that). First I studied in Edinburgh, then in Brighton, and they both have a lot to offer in terms of both culture and countryside. Anyway, it was very interesting to read and it gives some food for thought.

LikeLike