I’ve been thinking a lot more about time management moving into the 2nd year of my PhD. Last week, I mentioned that ‘publications’, as an overall concept, perhaps merits its own blog post. And here it is!

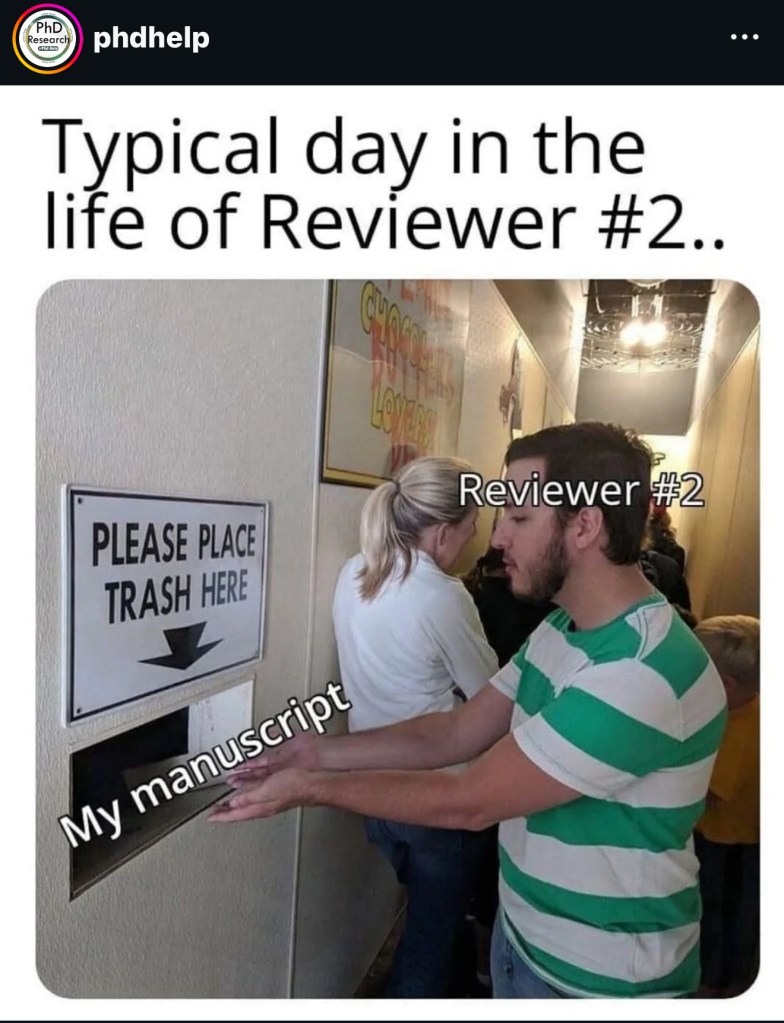

We are all familiar with ‘publishing’ as a practice in academia: It’s largely seen as something you ‘have to do’ in order to advance in your academic career, land an academic job, or stay ‘relevant’ in your selected field. At the same time, publishing is a frequent source of woe for several academics: Playful jabs at ‘Reviewer 2′ play out on various forms of social media, colleagues’ automatic replies cry out, ‘I’m working toward a writing deadline and may be slower to reply’, and celebratory LinkedIn posts ring out when it’s all over and done with. The publication process requires much more than just academic rigour; they require a level of mental and emotional tenacity that doesn’t come easy to most.

The infamous ‘Reviewer 2’. Image courtesy of @phdhelp.

In this post, I’m reflecting back on my very first time going through the publication process for an academic journal and the many thoughts, questions, and concerns that came up as someone entirely new to this world.

Wait, we’re not getting paid?

One of the very first surprises I encountered when moving through the submission process for an academic journal article was the fact that authors don’t get paid for their time. Obviously, I can feel several of you nodding through the screen already, but it’s worth taking a step back to consider the amount of unpaid labour that goes into publishing. More often than not, it’s not just authors that go unpaid, but peer reviewers and editors do too. The justification for this is that, as a researcher belonging to an academic institution, publication is an obligation that is embedded into your contract as a work-related responsibility. This disregards, however, the growing number of scholars that are intentionally choosing the route of ‘independent researcher’. This also fails to account for (as so often happens in academic contexts) the true time commitment required to bring an article through the publication process.

There is no single solution here that satisfies all parties: Increase transparency in academic research contracts, and this issue still stands for independent researchers. Advocate for journals to pay their people for their time, and the paywalls only get higher, costs to run journals soar, and several would frankly be put ‘out of business’.

It’s going to take how long?

In a SGSAH workshop I attended last year on ‘Publishing in Film and Media Studies’, it was stated that the average time it takes to publish a standard research article for an academic journal in the humanities was anywhere from 2 to 3 years. As someone who has been through this process, I can attest to this: My abstract for said article was submitted to the journal in October 2022, went to peer review in June 2024, and passed peer review in September 2024, for a November 2024 publication. The extremely long lead times for the arts and humanities1 is partially due to the issue raised above: nobody is getting paid for the work being done, and timelines need to account for the generosity of people’s time.

On the other hand, this long lead time can be difficult and frustrating, especially so for early career researchers, who may find their academic affiliation up in the air in 2-3 years’ time. Additionally, this is partially the reason why the arts and humanities are often ‘playing catch up’2 when compared to other disciplines. While an argument can be made that this only adds to the depth and rigour of publications in our field, there still seem to be more cons than pros regarding timelines.

Publication: A process so consuming they made a party game out of it! Image courtesy of https://publishorperish.games/.

Peer review? What, how, and why?

No one properly sat me down and explained what peer review was or what it would look like. Much of my first peer review was a game of ‘smile and nod’. Even though it is literally what it says on the tin – a group of your ‘peers’ will be assigned to review your paper – I was in denial that this was actually the case. Perhaps this is because the peer review process is actually very confrontational: In almost all cases (blind peer review), neither party will know who the other is, and that veil of anonymity can lead reviewers to criticism so harsh that even the most capable authors might find their confidence shaken, ego bruised. If you don’t believe me, look at any number of ‘Reviewer 2’ memes circulating on the Internet.

So what are they good for anyway?

Most seasoned academics – even those with a slew of successful publications – will agree that academic publication is a far from perfect system. So why do we publish in the first place? Like the eternal ‘assessment crisis’ (Are exams really the best way to ascertain a student’s progress? Are traditional marking schemes well-equipped to tell educators how much students have learned over the length of their course?), the general consensus tends to be that, while the system is fraught, we have not yet found another one that is better. So until then, we will have to continue publishing and deal with the consequences that come with it: unfair labour practises, unrealistic timelines, and unlikeable methods for retaining the rigour and ingenuity that should be the ‘bog standard’ for academic research.

Image courtesy of @clairlemon on Twitter/X.