Following Grace Wright‘s contribution to the Blog about zine-making, guest blogger Lucy Howie shares notes from their SGSAH-supported residency at Cove Park in Scotland.

During my Cove Park residency in September 2025, I wrote down the following sentence in my personal notebook: ‘peace and time are the defining elements of the residency’.

I arrived at Cove Park just following a two-month leave of absence. The previous year had been tumultuous partly due to my uncertain and changing renting situation at the time. I saw the residency as an opportunity to find my feet at the beginning of my final year of thesis writing. The residency offered an entire week of uninterrupted time to work on the fourth chapter of my PhD dissertation.

Over the last three years my research, archival work and internships have led me to stay in a variety of places including big cities like London and Toronto, as well as more insular University towns like St Andrews and Cambridge. Moving between these contrasting environments is enriching and dynamic, but I have also found that it can be difficult to find the steady ground each day that I require to write my dissertation.

Residents at Cove Park are offered a self-sufficient ‘cube’ with a double bed, a sofa, a fully equipped kitchen, and a desk. Every cube is oriented to face Loch Long. The floor to ceiling glass sliding doors of my cube provided the dramatic view over the hills and across the water. Beinn Ruach and the hills behind Ardintinny sweep across to a centre point in my view. ‘I feel far away from my daily life in London,’ I wrote down in my notebook.

Cove Park is situated on the west side of a peninsula on the west coast of Scotland. In the central Jacobs building I heard someone say that being on residency at Cove Park is like having everything behind you, metaphorically and in terms of the landscape, as you look out over the water and the distant hills. From my cube at the edge of the site I sat at my desk which looked over the unobstructed view, reading, planning and thinking about my fourth chapter, and feeling that I could leave the noise of everyday life behind me while I focused.

Several of the women photographers who feature in my dissertation project faced pressures of access to space and time during their working lives. Photographic practice specifically requires access to darkroom facilities, which can be expensive and time consuming to set up, to develop photographic negatives and produce prints. While some photographers were able to create make-shift darkrooms in their homes, others relied on community darkroom spaces housed in independent photography galleries, community centres and charities. In the 1980s, the South Asian London-based photographer Samena Rana campaigned for a wheelchair accessible darkroom to be opened at her local photography gallery, Camerawork, which successfully opened in 1985 owing to her persistence and sustained work with the disability arts organisation SHAPE.

For Samena, finally having access to a darkroom that was easy to travel to in London was transformative for her practice. She described the bliss she felt having total control over her photographic printing process, and the excitement she felt to finally spend her time and energy ‘on doing the work instead of finding access and persuading people that it’s a good idea to invest in darkrooms which can be used by people with disabilities.’ Samena Rana’s story is one which concerns the structural barriers faced by disabled people when finding reliable and accessible spaces to work creatively. Rana’s case is not unique, and is also one inflected by race, gender and class.

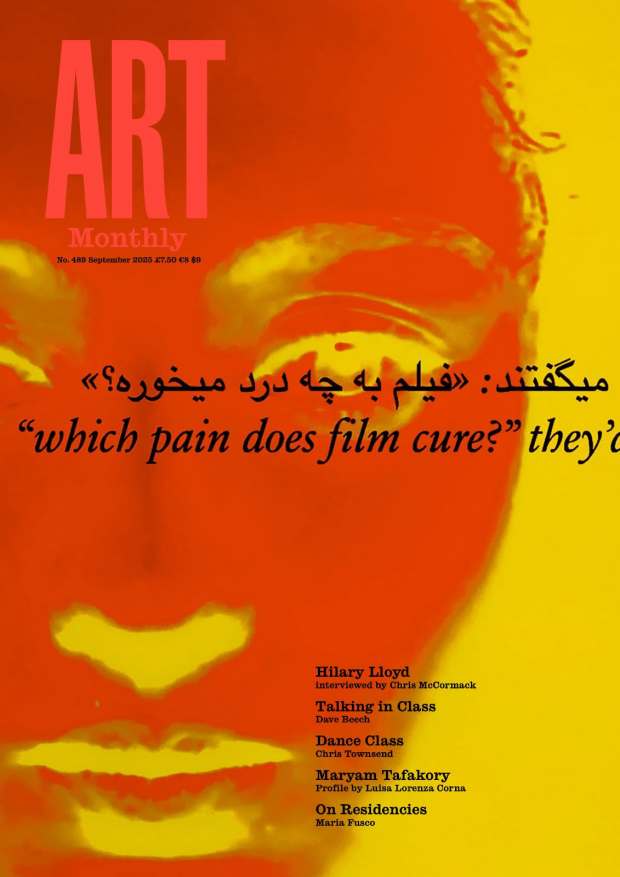

As I was plunged back into ‘real life’ (as noted down in my notebook) on the train home from Cove Park, I read Maria Fusco’s essay ‘On Residencies’ that had just been published in the most recent issue of Art Monthly. Fusco’s reflections shattered my romanticised image of the artist or academic residency as offering a utopian ideal separate from ‘real life’ and the ecosystem of academia and the market. ‘Being on residency is not a retreat,’ Fusco asserts, they are a ‘privilege’ and a ‘meritocracy’. Residencies are tied to those systems of the market and the academy because they are primarily centred around production. Residencies tend only to be available to those who have institutional backing and involve a highly competitive application process. ‘[Y]ou are competing for time,’ Fusco writes.

Re-reading my diary entries from the week of my residency, I was struck by my reflections on the pressure to make the most of my university education since leaving school. I have developed a bad habit of trying to fit in too much and then worrying about not getting my work finished on time, and I know I’m not alone in doing this. I often feel pressure to work as fast as possible, even when my work involves reading and understanding the difficult and sometimes knotty arguments of academic texts. Maria Fusco writes in her Art Monthly article that, ‘[t]he residency experience is therefore, over time, a good way to learning something specific about your needs, as a maker and perhaps as a person.’

Fusco’s comment encapsulates what I have found to be most impactful about my time at Cove Park. I have since tried to rethink the ways that I can firstly be led by curiosity and honesty in my work, rather than by fear of failure to produce. Even when it’s not possible fully control the consistency of my workspace, I have practiced consciously slowing down my working process, putting the deadline date to the back of my mind, and allowing myself more time to complete a task. This is one way I have managed to find that sense of ‘peace and time’ with my work as I move forward with the final year of work on my thesis.

Lucy Howie is an art historian based between Fife and London. She is a SGSAH-funded PhD candidate at the University of St Andrews. Her thesis titled, ‘Disability, Sexuality and the Politics of Representation: Photography in 1980s-1990s Britain,’ explores where queer and feminist photographers negotiated photo-theoretical debates on perceptions of normalcy and the body in the context of disability activism, HIV/AIDS, and Section 28. In 2024, Lucy was Research Associate at the Women’s Art Collection, University of Cambridge and the Singer Doctoral Fellow at the Image Centre, Toronto Metropolitan University. She has previously held positions at Kettle’s Yard in Cambridge and the V&A Dundee, and she has taught on 20th century art histories at the University of St Andrews. Her dissertation research has been supported by the Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art, Association for Art History, and British Art Network. You can find out more about Lucy’s work here.