In this blog, resident SGSAH blogger, Beth Price, talks through how she chose her PhD project, working in the field of Chinese Studies, and the ever-expanding list of questions she is trying to answer.

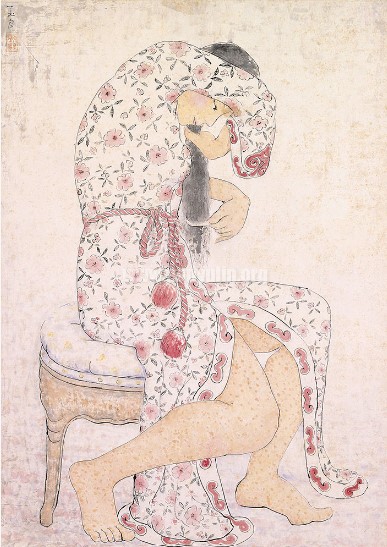

My PhD research sort-of follows my master’s thesis, which focused on the Chinese artist, Pan Yuliang (1895 – 1977). I first came across Pan’s work and life-story from a Twitter thread by the historian, Dr Kate Lister (content note: nude paintings). Pan’s work immediately grabbed me, her style was so obviously a melding of traditional Chinese ink painting and Western nudes, but the women in her paintings looked real.

Her life-story was also fascinating; sold to a brothel by her uncle, becoming the second wife of a diplomat, rubbing shoulders with radical reformers in China and great artists in Europe, and eventually being exiled from her homeland, her life almost seemed like the embodiment of China’s tumultuous twentieth century.

But for some reason, almost no one had written about her. There were a handful of English-language journal articles, a couple of book chapters, a magazine article or two, but nothing like the amount of analysis given to other artists from the same period. Even more annoyingly, despite the fact that her works outnumber Van Gogh, most of the articles about her focused on what was done to her, not what she did. I set about re-centring Pan in her story, starting with her paintings and finding the threads which tied her work to her life in exile in Paris, her experience as a second wife, and her youth spent in revolutionary Shanghai.

And it is revolutionary Shanghai that I wanted to keep exploring with a PhD. In 1911, the last emperor of China was deposed, and until the Communist party seized power in 1949, China was a republic, and a rapidly modernising one at that. To the revolutionaries of the New Culture Movement and the May Fourth Movement, “modernity” meant widening education, civil rights, the dismantling of old social hierarchies, and building a new China which could stand in its own right on the world stage. At the centre of all the theorising and proselytising were women.

In contrast to the dearth of writing on Pan Yuliang’s life and works, there is so much literature on women in Republican China that you have to wade through to find a new angle. Women as writers, consumers, revolutionaries, and mothers. Women as seen by themselves, by men, by government officials, and by authors. Women’s hair, hands, faces, and feet. Almost every aspect has been investigated to some degree.

But for all the discussion about how women represented China’s hope for the future, I found that there was hardly anything about the impact of all this on women. When women’s body parts and social roles are analysed in isolation, it is hard to get a sense of the cumulative effect on women’s lives or on changing gender roles. I decided to look at the whole body, specifically the whole naked body.

Unlike in Western culture, where nude figures had been the pinnacle of art and medical students had been carving up bodies for centuries, the naked body did not really exist in Chinese culture. Of course it technically did – people have gone unclothed for various reasons since we became people – but there was no tradition of representing the nude body in non-erotic art or media, and the conceptualisation of health and bodily identity was rooted far more in concepts of qi and spiritual balance than in anatomical excellence.

In this context, the radical nature of Pan Yuliang’s paintings of naked women is perhaps more obvious. The revolutionary thinkers of the Republican Era explicitly rejected traditional Chinese medicine and Confucian culture, introducing (and promoting) a Western-informed conceptualisation of the body. In the new consumer economy, advertisers and industry leaders quickly took to using scantily clad sexy women as the favoured method to sell products, often backed by “scientific” claims.

It is this interaction between culture and science which I am investigating in my PhD. Whether in high art, school textbooks, or provocative adverts for toiletries, naked women’s bodies became a feature of Republican China. But the explosion of media depictions did not lead to wide-scale social liberation of women. Quite the opposite in fact; modernity’s focus on women brought new ways of exerting social control over them. “New Woman” was the feminised moral ideal of China’s future, but “Modern Girl” was sexualised just as much as she was condemned for her sexuality.

The belief that Republican China was “modernising” and becoming a new society coming hand-in-hand with new patriarchal social control over women is where I began my research. Through examining art, magazines, school textbooks, medical research and calendars, my aim is to answer my ever-growing list of spin-off questions, like is “modernity” inherently patriarchal? How are bodies and gender identities used to establish and reinforce social order? What links media, advertising, and medicine when it comes to the public concept of “woman”?

Answers to all the above, and undoubtedly more, pending. For now, I’m going to re-watch the Barbie movie and eat dumplings. It counts as research.

Beth Price is a 1st year PhD researcher in Chinese Studies at the University of Edinburgh. Her research explores nudity and the female body in media, arts and popularised medical science during the Republican Period in China (1911 – 1949) in the context of feminism, semi-colonialism, and a new transcultural medical discourse. Find her other writing, outreach, and community education resources at @breakdown_education on Instagram.