This week, guest blogger Callum Simpson shares his story about starting a PhD, leaving a PhD, and re-discovering his passion in the process…

I left academia because I could no longer financially afford to continue as a PhD candidate. Unfortunately, I too contributed to my inability to remain in academia; as did – in my opinion – several schools, councils, and funding bodies.

In this month’s SGSAH blog, coincidentally the expected end date of my studies had I completed them, I intend not only to speak of past funding related frustrations, but rather of the lessons I have carried with me from academia and into my professional life today.

The following words are guided by three claims: a reminder to love your subject matter, to acknowledge others, and to find in failure a form of triumph.

I Almost Became an Organic Farmer

My route into academia was atypical. I was a middling student, without a vocation and duly left school for full-time work. In the tedium, constant surveillance, and gruelling targets of a string of call centre jobs – I learned quickly what I did not want to do. With funds gleaned from this work, I travelled with a friend to Italy, volunteering at an agriturismo in Tuscany before working on the grounds of Borgo Pignano, a luxury countryside hotel as an organic farmer. It was in downtime there, with friends and colleagues, watching Crimes and Misdemeanours (Allen, 1989), Withnail & I (Robinson, 1987), and crucially In the Loop (Iannucci, 2009), I realised I wanted to learn more, to return home and to work towards going to university rather than staying on in Italy; digging ditches, planting tomatoes, and keeping bees. What I failed to appreciate then was the subject of my fascination was indeed film, a failing made all the more remarkable as this missed revelatory moment coincided with a chance meeting in Pignano with Armando Iannucci himself, writer and director of In the Loop. As if to prove my shock and awe, please see my startled face in this photograph, replete with background cat, my only evidence of time spent in the company of a comedy hero of mine.

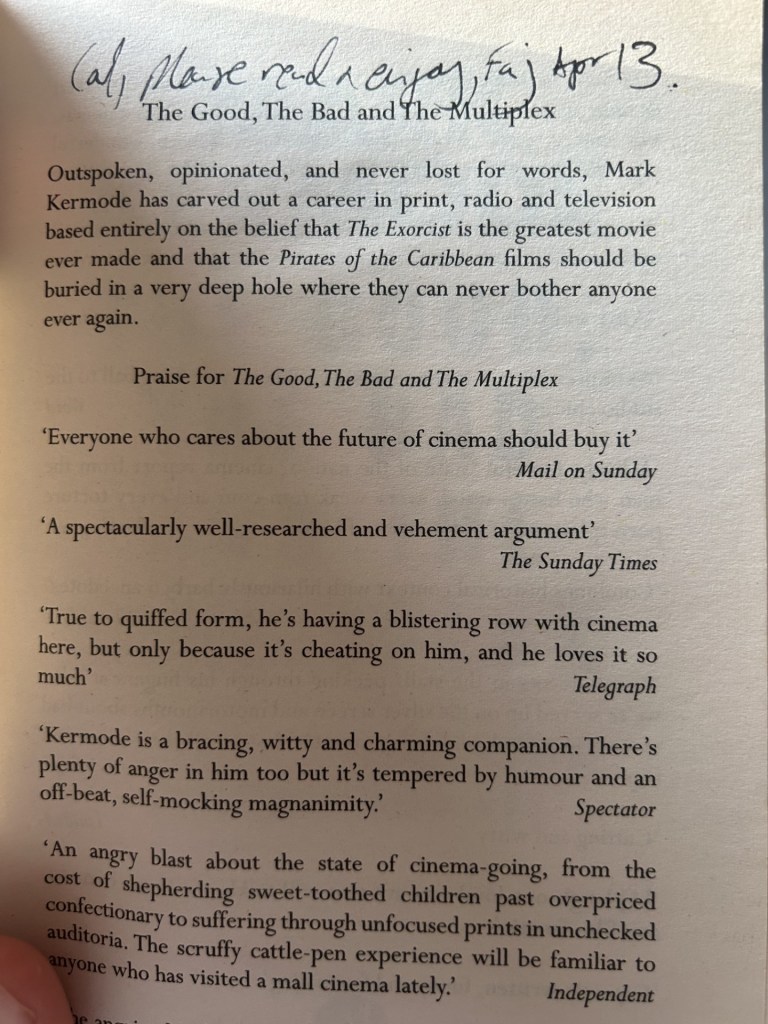

Throughout a year at college and afterwards when applying to university, I continued to think of film as in some way fanciful, an outlier amongst more seriously minded options for further study. What I misinterpreted however was my love for film. From projected screenings at home of Kill Bill: Vol 1. (Tarantino, 2003) to episodes of Frasier (1993-2004), regular trips to the Glasgow Film Theatre, not to mention the frequent encouragement of family and friends, others acknowledged in me what I failed to see in myself: I could – that is to say, should – become a student of film. See the inscription in this inside book cover of film critic Mark Kermode’s The Good, The Bad and the Multiplex (Kermode, 2011) written by my Dad, the year before I began my undergraduate studies in film.

The Permanent Effects of Acknowledgment

In her book: Stanley Cavell and Film: Scepticism and Self-Reliance at the Cinema (Wheatley, 2019) Catherine Wheatley tells of a crucial formative experience from Cavell’s early life. When a high-school teacher lavished praise on a film review of his, first in reading it aloud to his classmates before superseding a convoluted grading system to award him the highest possible marks, Wheatley writes: “[t]he teacher’s praise for Cavell’s work seems to have had a lasting effect, informing his imagination ‘of the permanent effects an act of acknowledgment may have” (Wheatley, 2019, p. 6). I too felt similar effects as an undergraduate student at the University of Stirling. Three teachers left an indelible mark: Dr. Cristina Johnston, for encouraging I transfer from a Film and Media degree programme to Global Cinema and Culture; Professor (emeritus) Bill Marshall, for supporting my writing; and Professor Elizabeth Ezra for praising my dissertation and discussing options for further study before I had graduated. I am indebted to them all. It is little wonder I returned to Stirling, after my Masters year to study Cavell’s notion of acknowledgment and cinematic influence under Elizabeth’s supervision as a PhD candidate; itself an act of acknowledgment.

While the above words are threaded with a form of happy accident many of you are surely familiar with, my time in academia was equally marked by misfortune.

Finding a Form of Triumph in Failure

Days before my undergraduate graduation Global Cinema and Culture ceased to be separate degree programme at Stirling. This was something of a bellwether for a run of disappointments. Self-financing my Masters at the University of Edinburgh, I had begun to struggle with the grind of a condensed working week, accommodating for 5am wakeup calls and work in the retail sector. Balancing full-time study with part-time work, endless commuting time and seesawing priorities where in order to partake in higher education, I had to work; I gradually fell out of love with my subject. While fully funded students were paid to think, I was paid to unload crates of clothes or, put differently, my part time endeavour paid, my full-time endeavour did not.

At the time of my eventual withdrawal from my PhD, SGSAH’s numbers, in particular, were stark: less than 60 awards and very few awards in Film Studies.1 This I later discovered had been the case for several years. Had I known the chances of a successful studentship award in my discipline were very low2, as opposed to merely competitive, I would likely not have embarked on this course of study to begin with. My chief gripe was the lack of transparency, and a clear delineation of which proposals were successful and why – a criticism shared with other schools and funding bodies but one in which SGSAH looks to have partially remedied since. Coupled with COVID-19 and further funding applications gone awry, my enthusiasm for film studies gradually petered out. Imposter syndrome took root again, much like in my inability to see film as a path to future study and success, I started to think neither academia nor film were for me. Perhaps only one of these tenets is true.

Three years on, I now contribute to a film team as a producer. My knowledge of the logistical and technical side of filmmaking has accelerated, and my work in conjunction with video editors in post-production has helped debunk for me the genius myth of the auteur. I have benefitted greatly from theoretical lessons learnt studying film at university and I have carried into my work a forensic attention to detail as well as a self-reliance, which I attribute to my time in academia.

Aided by this very exercise, I have come to see consider my time in academia fondly and most importantly, I have rediscovered my love for film through a proximity to those who create it. For me, the three guiding claims of these words are something of a salve: and to those who have read these words; I hope they have similarly permanent effect for you.

Callum is a digital video producer for award-winning creative, learning and communications agency Mediazoo. For one client, Swiss independent academic institute IMD, Callum contributes to a team of creatives in Lausanne and Glasgow as a production manager and copywriter.

Callum holds a first-class Bachelor of Arts with Honours (BA Hons) in Global Cinema and Culture from the University of Stirling in 2018 and graduated with distinction in 2019 from the University of Edinburgh with a Master of Science (MSc) in Film Studies. In 2021/2, Callum was enrolled as a Film Studies PhD candidate at the University of Stirling.

Callum is contactable via email at: callumsimpson17@hotmail.co.uk, active on LinkedIn and on Letterboxd at: https://boxd.it/1KkC7.

- It is worth noting here that SGSAH’s application figures are not published. However, each of SGSAH’s 10 member HEIs has the opportunity to make up to 60 applications each year. ↩︎

- Publisher’s note: According to SGSAH’s Director, the acceptance rate for funding applications tends to range from 20% to 25% year-on-year. ↩︎