Guest blogger Marie-Chantal Hamrock shares their research-based artistic practice, exploring maritime cultures in Aberdeen, Peterhead and Fraserburgh.

My PhD project Class, Place, and Speculative Fictions: A Study of the North-East of Scotland’s Maritime Cultures, explores the fishing industry in Aberdeen, Peterhead and Fraserburgh. Speculative Fiction is an important generative method within this line of enquiry, as a creative device through which imaginary dimensions and alternative realities provide opportunities to speculate on the past, present and future of fishing in these places and within these specific contexts.

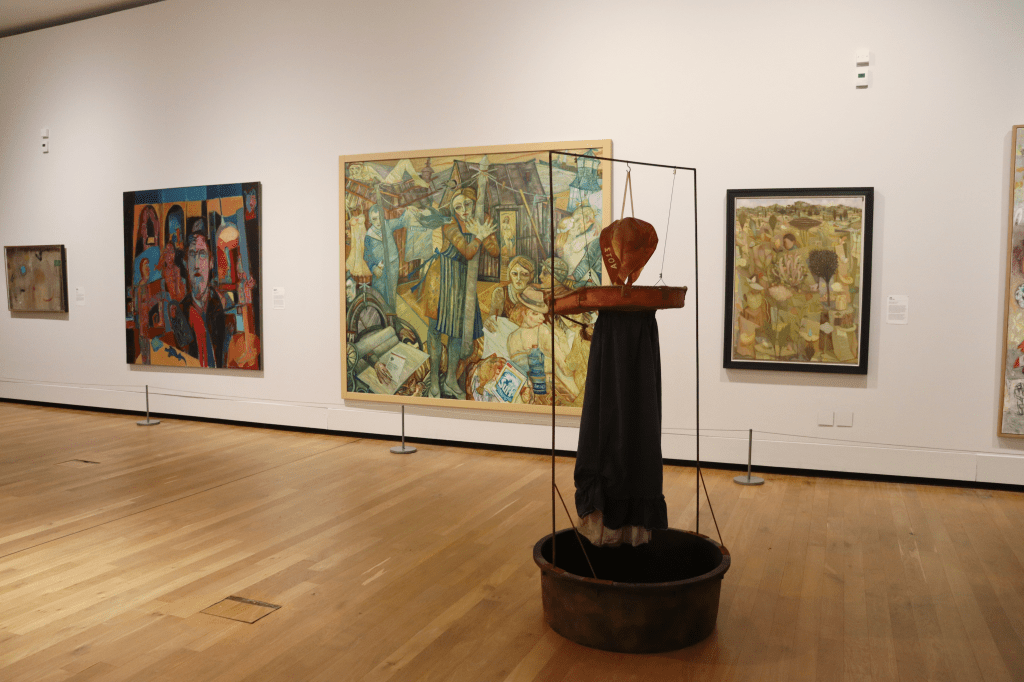

Eeley Betty (2025), my moving image and installation piece which is currently on display in Aberdeen Art Gallery as part of the Gray’s 140 Years exhibition employs speculative fiction to explore some of the themes described above. This work was commissioned in response to The Drying Green by Joyce Cairns, a narrative painting from 1992 set in Footdee, one of the old fishing villages of Aberdeen.

About a year ago, I came across The East Neuk Chronicles by William Skene, which were a series of stories about characters in the East End of Aberdeen between the years of 1840-1860, published in the Aberdeen Evening Express in 1896. One such character who captured my imagination in line with some of the research questions at hand was Eeley Betty, a woman who worked in a whale blubber yard on York Street in Footdee.

‘I recollect another Footdee worthy, the well-known Eeley (oily) Betty…’

In his original text, Skene wrote that Eeley Betty wore a ‘blue baize petticoat’ and that whenever her oil lamp required replenishing, she would take off her petticoat, dip it in the blubber vat at work and carry it home. When Eeley got home she would wring the whale oil out of her skirt, pour it into her oil lamp, and hang it up to dry for the night before putting it on again the next morning.

The protagonist’s name, Eeley Betty, is evidently illustrative in the sense that she did work in the industrial production of whale oil, and she was known for dipping her petticoat in the blubber vat. However, there is perhaps a classist double meaning to the descriptor eeley/oily. Throughout the story, Eeley is portrayed as being slick, wily, and cunning, on two instances tricking other characters into giving her free snuff for her pipe and coal for her fire.

Layered at a deeper level in this seemingly comical story of a local eccentric is a painful image of a working-class woman coming home alone, to light a lamp with stolen oil. Not only is this a moving story of ingenuity and unapologetic idiosyncrasy, Eeley’s actions, act as a fascinating moment of foreshadowing to contemporary issues around oil extraction, energy transition and even the current realities of fuel poverty – all of which are acutely felt in Aberdeen.

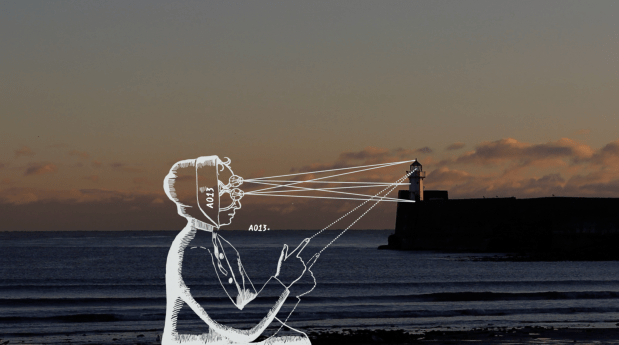

Through employing speculative fiction, the film takes the action of wringing the whale oil out to a new extreme, where Eeley saves a little bit of oil to drink for herself, eventually emitting light from her own mouth, emphasising her independence and ingenuity in the face of stark poverty. By projecting light out of her mouth, Eeley is able to spectrally slip through time, continuing to exist along the harbour, even in diminished forms. In fact, Eeley (voiced by Ellie-Jane Ritchie) eventually takes over the narration of the film entirely and claims agency over the fiction in itself when she says, ‘I am the dream-reality of the past’.

The film utilises archival footage of whaling from Whaling Afloat and Ashore by Robert W. Paul (1908), folk song (The Bonnie Ship the Diamond performed by local folk singer David Hunter), speculative re-enactment and animation. The drawings and animation exist somewhere between the fantastical and the diagram, acting as reminders of absence and defunct industries, while imbuing the archival material with an ethereal and dream-like quality. In a sense these parts of the film reactivate and re-imagine an archive which is seldom seen in Aberdeen, especially in relation to its history in fishing.

Although the figure of Eeley Betty is not part of the fishing industry as we know it today, her character acts as a fascinating personification of whaling, and the ways in which maritime cultures might be speculatively embodied by female characters whose labour and livelihoods were obfuscated over time. The re-telling of Eeley Betty re-surfaces a character who had slipped out of the mainstream cultural memory of Aberdeen’s maritime history. By un-silencing this poignant story, the counter-memory and resulting speculative fiction demonstrate the importance of interrogating dominant imaginaries of place and class both locally and further afield.

Gray’s School of Art: 140 Years- Never make a head bigger than a melon, curated by Sally Reaper and Judith Winter, is at Aberdeen Art Gallery until 12 April 2026.

Marie-Chantal Hamrock is a practice-based PhD candidate at Gray’s School of Art in Aberdeen. Her project is supervised by Dr. Jon Blackwood and Dr. Laura Leuzzi.