This week, PhD Researcher Isobel Harvey continues a three-part series reflecting on the 2025 EARTH Scholarship Programme. In this post, she reflects on the benefits of engaging with different disciplines throughout the programme and how this has fed directly back into her own multidisciplinary research…

Hello SGSAH Community!

I am a first year PhD student at the University of Glasgow studying the archaeology and palaeoenvironments of Scottish peatlands, and I was incredibly lucky to be one of the Scotland-based scholars on this year’s EARTH Scholars Cohort Development Programme. This programme was inherently multidisciplinary, from its scope bringing together twenty different research students across the environmental humanities, to the series of lectures, workshops and field trips which covered everything from handling Mesolithic microliths to critiquing nineteenth century nautical maps.

For me, this chance to dip into a range of different disciplines was one of the major highlights of the programme. It granted me the space to spend several hours playing around with different methodologies and frameworks, using these different subjects like a sandbox to try out novel (to me) approaches to research. The relatively low-stakes nature of these engagements (I was not going to fail my viva if I did not understand an oceanography concept) meant that I was free to explore these ideas in a whole new way.

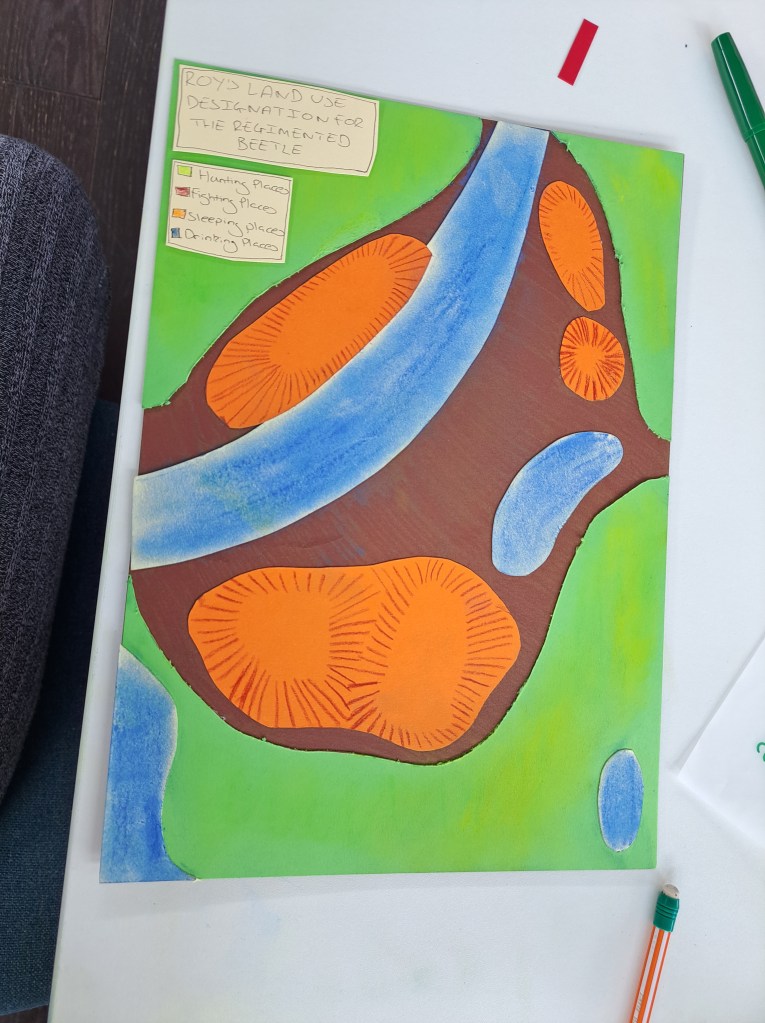

The session ran by the University of Strathclyde on interdisciplinary and multidisciplinary working was incredibly insightful for thinking through how to embed these practices into my own work, as well as the key difference between the two workflows, and when one might be more suitable than the other. As part of this session, we were set to approach each other’s research projects from our own disciplines, thinking about what questions we could ask and how we might answer them, before switching to think about our own research but within another’s discipline. I found this exercise very insightful, as well as a lot of fun, for examining my rationale for my own research questions and methods, and reflecting on alternative approaches to some of the problems I was facing with my project.

I also learnt an incredible amount from this programme. The range of scholars, with their different approaches and disciplinary backgrounds, as well as those of the programme facilitators at each HEI, meant I was always hearing about a new name or paper, and often frantically scribbling it down to look up later. And there were plenty of spaces within the programme to discuss these ideas with my fellow scholars, over organised dinners or impromptu trips to a local exhibition after the day’s scheduled events. These discussions highlighted the wonderful community that exists in the environmental humanities- there are so many people working in such creative ways to combat issues such as the current climate crisis. One of the particularly striking things to emerge from these discussions was the frequency of my fellow researchers who had moved to a new discipline or sub-discipline for their PhD; for myself, I had moved into environmental archaeology from a background in organic material culture. I found it interesting to hear how others had managed this transition, and the new opportunities that they had discovered through this process. It often seemed to be the case that they kept their feet in both disciplines to some extent, combining their previous experiences and knowledge with the new debates and methods they were encountering. I was really inspired by the ability of my fellow scholars to blend disciplines that, at times, were radically different from each other.

Throughout the programme I found myself responding to the different disciplines, thinking about how I could embed these new and creative approaches I was learning about to my own work. One of the ideas that most stuck with me was how my fellow scholars were thinking about and responding to the Anthropocene- a question which has now woven its way into my own methodology. Having the space in this programme to step outside of the day-to-day workings of my own discipline, having the chance to think, and learn, and get creative with using other disciplinary frameworks, has allowed me to approach my own research questions in a new light, asking what is fully possible to achieve with my PhD.

This is the second entry in a series of three pieces provided by participants of the EARTH Scholarship Programme for 2025. Next week, Zahra Tootonsab, who examines the relationship between sheltering and decolonial flourishing at McMaster University in Canada, and David Ogoru who researches the environmental history of coastal communities in Nigeria and West Africa at Brown in the US – will reflect upon their respective work on the ethics of interdisciplinary research.

Isobel Harvey is just coming to the end of the first year of their SGSAH-funded CDA with the Universities of Glasgow and Stirling and the National Trust for Scotland, ‘A Cultural and Natural History of Scotland’s Peatlands’. This project combines landscape archaeology, social history, and palaeoecology to tell the ‘deep-time’ narrative of upland blanket bogs under the care of the National Trust for Scotland. Issy is interested in people-peatland relationships, experimental approaches to the study of organic material culture, and how the use and socialisation of natural resources may have influenced past people’s identities.

You can follow Issy’s research through the following channels:

- Instagram: @peatyphd

- Research Profile: https://www.gla.ac.uk/pgrs/isobelharvey/